Afia Salam and Rafi ul Haq

Naseer Mohammad Brohi has a faraway look in his eyes … Sitting on his wooden cot woven with rope called charpai, on a beautifully embellished rilli, the patchwork bedspread Sindh villages are famous for, his eyes span the undulating vista before him.

He is the head of the village of Chhato Chand made up of about 100 households, all kin to each other. In that capacity he bears the weight of responsibility of not only looking out for his people, but also their assets, the most precious of which are the about 500 heads of cattle that sustain all of them.

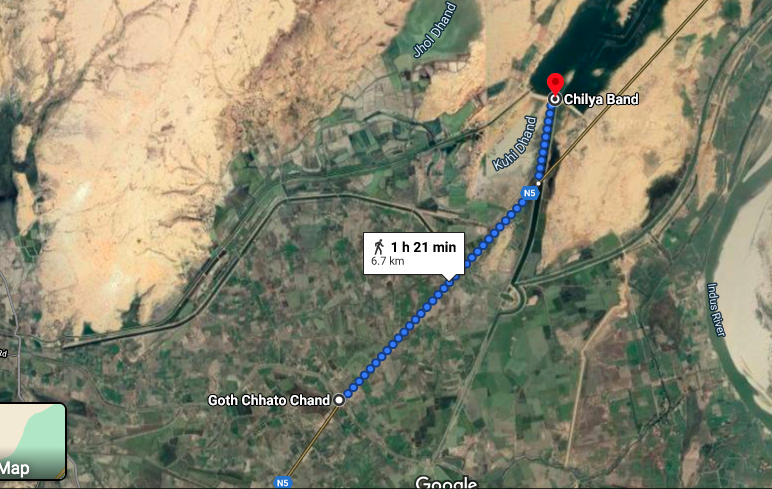

He has recently arrived with his village folk in Jabal, an undulating rangeland near Jhimpir in Thatta district.

His arrival here is continuation of a norm he has seen his elders follow. They too moved from their settled village closer to the town of Thatta.

He does not know terms like climate change or migration. He just knows that some generations before him, his pastoral ancestors trekked from Pandrani in Balochistan to Thatta, the thriving capital of the hospitable, accepting land of Sindh, and settled near the Keenjhar lake in Jabal, beyond Jhampir.

Life in the area they had come from had become difficult due to the scarcity of food for their livestock, so they came to the land drained by the Indus river, and settled in an area that resembled the undulating terrain they had left behind.

In Sindhi language, Jabal means a hill or higher ground, and here they could reminisce about the homeland they had migrated from. These Brohi tribesmen started their life anew, while still following their traditional pastoral lifestyle.

Five generations later, livestock still is the mainstay of Naseer Brohi’s kinfolk. It provides them with food as well as cash. They sell milk of their cows, al beit at a very exploitative, low rate to a middleman. He buys it off them for about Rs. 40 per litre, whereas the going rate in the city is at least four times higher.

They are dependent on him coming to collect the milk and sell it on the town market, and agree to this low price because the alternative would mean taking the milk to the market every day from their relatively remote location.

The goat milk does not have a great demand in market, so that is used for their own consumption, especially for their children by the villagers.

He knows that the village is where they must return to when things become better. That is why he has left some of his trusted people to look after their homes and assets despite the damage they had suffered due to torrential rain.

Most of the mud houses and thatch abodes known locally as chapras, had collapsed in the rain.

Only the few brick and mortar houses built by the relatively more affluent of the community remained standing.

But for all intents and purposes, the village was their home, while Jabal, where they made their temporary dwellings, was a place of refuge from scarcity and paucity of cash that could enable them to but fodder for their cattle.

This area, which was chosen by his ancestors, provides him and his people as refuge where they can eke out a subsistence living along with their animals whenever they have to leave the village due to adverse climatic conditions.

He sits there watching his womenfolk busy in their household chores of tending to the cattle, fetching water and milking the cattle while the children play around the open space or sit huddled in clusters.

While acknowledging the benefits of the move to their ancestral land, Naseer is mindful of a major downside of this migration. He is sad because of the disruption in the children’s education. Because this is not a revenue village, there is no government school here for them.

Jabal is in a pocket of invisibility. There is a winding road about 35 kilometres away from the main highway. The fruits of development do not ripen along that small road. So no school, nor any Basic Health Unit. There is a wind turbine set up by a Chinese company within sight. But no job opportunities for this community.

Such migration by the community may last for months and this disruption is not conducive to continuing school education. In fact, across Sindh, such migrations are the reason for the high rate of school drop outs.

He sees the frequent to and fro as detrimental to the continuity of education for the children. He realizes its importance for their future because despite being the Imam or the prayer leader of the local mosque, he missed out on any formal education.

Interestingly, but not surprisingly, this concern does not extend to the girls of the community. Culturally there is still resistance to the concept of sending girls to school. One reason is the responsibility put on their shoulders for all house chores, especially fetching of water which consumes the better part of their day.

The area of Jabal is their fall back option. The only Plan B of the community for when the going gets tough and they cannot sustain their livestock at their permanent abode.

The very limited options available mean that when climate is not kind to their livestock, they move, because their lives are inexorably linked with the health of their cattle.

He has a satisfied yet wistful look on his face as he sees his livestock forage on the plentiful bushes and grass available as fodder for them; the main reason for having migrating to Jabal.

Life was much more comfortable in the village where they had access to running water and transport on the main road. Despite this they were forced to move to this relatively remote area they could call their own..

The recent rains had been a boon and there was food aplenty in Jabal for the cattle. Presence of medicinal herbs and bushes meant they are able to take care of minor ailments as knowledge about their healing properties had been handed down to them by their elders.

Besides availability of natural vegetation, the land made fertile by recent rains also allows the villagers to grow some corn, which is a quick turn around crop.

Migration to Jabal is a tough trade off. Life for the livestock may be better here but it is definitely more difficult for the people especially women. While they had access to running water in Chhato Chand , here the water source is quite far from the village.

They are dependent on the water that collects in a depression for household and livestock use. In Jabal they have to carry utensils and fetch water in them, which makes life additionally difficult.

He says despite these hardships, knowing that they at least have some ancestral land to move to when it becomes difficult to stay in their village is a blessing.

It is unlike the fate of many other communities who drift from place to place seeking food and forage, many times being displaced from where they set up a temporary abode because the landowner does not want them there. Those climate migrants are in a far more pitiable condition than Naseer’s Brohi clan.

He does point out to some encroachments on ‘their’ land which is in proximity of the KIV water supply scheme for Karachi.

He is however, not too worried about that fact that his clan does not hold any title deed, as over all these years, that has not posted a problem to his people making use of this place.

The beginning of ‘encroachment’ however, is reflective of plight of all indigineous people who run the risk of displacement from their ancestoral land simply because they hold no papers to back their claims over it.

Internationally, rights of the indigineous people are being recognized as legal and laws are being framed to encompass the legal as well as traditional rights.

Laws in Pakistan too continue to evolve and the need is to accelerate the process to bring the marginalized communities like the inhabitants of Chhato Chand into the mainstream. They should offer them security and peace of mind about the land they have called their own for generations.

In a similar manner, laws and policies need to be congnizant of the plight of the climigrants, whose number will continue to grow in the wake of slow onset disasters like desertification and drought.

Such changes force communities like Naseer’s ancestor to go in search of ‘greener pastures.’

The cataclysmic disasters such as storms, floods and excessive rainfall catch the eye because of the scale of damage and displacement and the immediacy of response required.

Such disasters blinds even policy makers to the population shifts that occur due to the slow onset disasters triggered by climate events in slow motion.

Such changes cause a bigger and longer duration displacement, which need to be dealt with because the pressure of the moving community, and their livestock on the new area’s ecology also needs to be mapped.

Resource depletion in one place may induce migration, but the pressure of the migrant community on the new location may cause depletion there too over a longer period of time… on the biodiversity, on the soil fertility, on the vegitative cover.

Sometimes it is not just the mere increase in population but the unchanged consumption habits of a community that can lead to resource depletion.

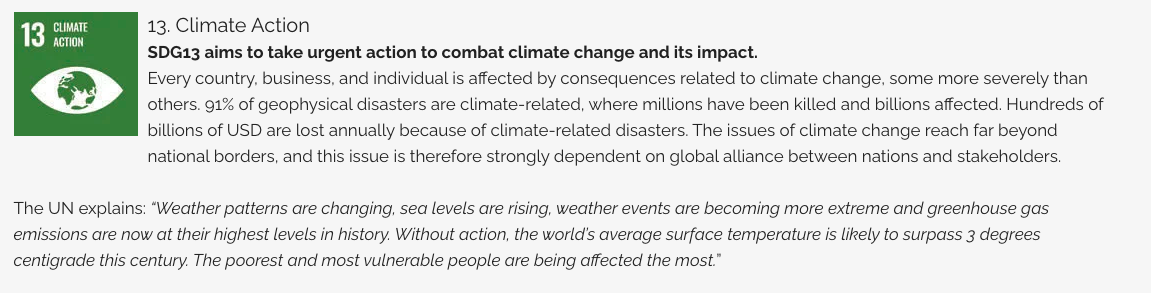

Right now, in the climate change conversation in Pakistan, these voices are unheard. There is hardly any reflection in the existing National Climate Change Policy.

Even the disaster management plans do not acknowledge and address the trend of climate induced migrations. They are mostly reactive, coming into action after a disaster has occurred.

Organizations like Islamic Relief Pakistan have been conducting research through academia to map out the extent and intensity of the problem. Climate Change adaptation and resilience building has been the core component of all its program and interventions.

Its VOCAL (Voices Organized for Climate Change Advocacy and Lobbying) campaign where in voices from the field are being brought to the fore has been conducted in conjunction with the University of Sindh, Centre for Coastal and Deltaic Studies (CCDS).

The research has mapped out several communities in Thatta and Badin, following an agrarian life as well as of fisherfolk, and traced clear indications of displacement induced by climate change.

Speaking about the programme Sarmad Iqbal, Advocacy and Campaigns specialists at IR, said VOCAL was initiated to strengthen the understanding of provincial and national Government departments, media, academic, lawyers, and faith leaders. The objective is to raise climate awareness and shed light on the issues from a multi-dimensional and multi-institutional perspectives.

It is imperative that the research findings gain resonance in the new documents and policy plans. The measures needed may fall under the umbrella of mitigation, adaptations, or climate action, which Pakistan claims to have met 10 years ahead of target, but unless the people on the ground reap the fruits of those actions through resource equity and justice, the achievement will ring hollow to them.

The inequities and injustices were thrown up during the unprecedented monsoon deluge of 2020 that impacted both urban and Southern rural Sindh. However there was wide chasm in the attention that urban disaster garnered in media, and subsequent response among the authorities, and the already marginalized, poor and dispossessed in rural areas.

While it is true that these inequities played out within the urban areas as well, seen by the way some parts of Karachi and Hyderabad gained the eyeballs through mainstream media, while others relied on attention garnered through what we can term as citizen journalism, it took a lot longer for people in the rural areas to receive attention, and relief.

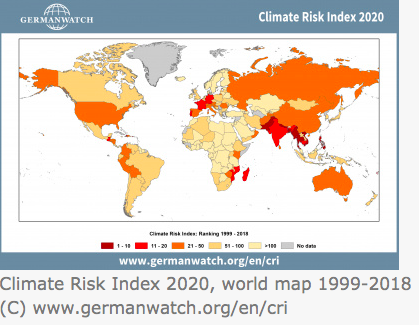

Pakistan is consistently appearing high on the global climate vulnerability index put out each year by GermanWatch.

The slow onset disasters set in motion by Climate change are likely to barrel into the ones whose frequency and ferocity is increasing, impacting large swathe of land and the people inhabiting it.

This is true for vulnerable areas of Pakistan ranging from the mountain ranges in the North vulnerable to GLOF (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods) or the desertification being witnessed in the Cholistan in Southern Punjab, Tharparkar in Sindh and large arid areas of Balochistan. We see no projections of the scale of human displacement and migration as a result of these phenomena which are likely to be exacerbated due to Climate Change.

Sindh is about to finalize its Climate Change policy. Now is the time to embed the factor of climate induced migration, map the locations of vulnerable communities and plan for their relocation where they can sustain their life with dignity.

Waqar Phulpoto, who is the focal person for Government of Sindh for the Climate Change policy when approached said the policy has almost been finalized but he will definitely be open to addressing the question of Climate Induced Migration to make it all encompassing and responsive policy.

There needs to be proactive engagement with organizations, community leaders and development sector personnel to make sure the policy response is adequate and just. This is also the only we will be able to meet our commitments to the whole range of Sustainable Development Goals, to which Pakistan signed on.

Because they all stream into each other, stand alone meeting of just one goal is not likely to help in meeting the objective that they have highlighted. It is in Pakistan’s own interest that all Climate Change measures be taken while keeping an eye on the SDGs, because they are as cross-sectoral as is Climate Change as a looming threat.

Only then we will be able to claim that we have the interest of Naseer Brohi and his community at heart.

Text: Afia Salam

Background information: Adnan and Rafi ul Haq

Photos contributed by: Adnan, Rafi ul Haq, Shabina Faraz, Fariha Fatima, Abdullah Rajpar

Videos contributes by: Sidrah Dar and Khalil

Video edits by: Fursid